Incontriamo Tania Pistone nel suo studio, occasione preziosa per poter osservare da vicino (e indossare) la sua recente produzione orafa, in dialogo con la sua ricerca pittorica.

SCROLL FOR ENGLISH VERSION

È sempre motivo di grande interesse osservare come un artista riesca a trasferire la propria poetica nelle diverse discipline, rispettandone i condizionamenti formali imposti dal supporto e dalla tecnica e, al contempo, mantenendo una coerenza di base: Tania Pistone, pittrice di talento che ha orientato la sua ricerca verso una decisa astrazione (un’astrazione ricca, argomentata, lontana da certe derive del minimalismo), ha saputo veicolare nel gioiello, con esiti del tutto originali, alcuni suoi specifici interessi, ormai cifre distintive della sua pittura.

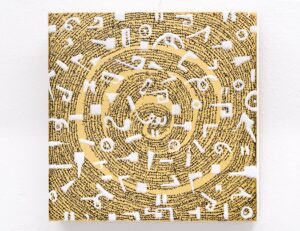

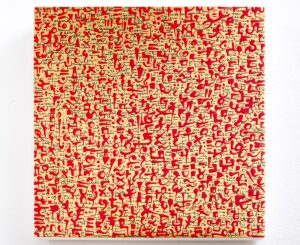

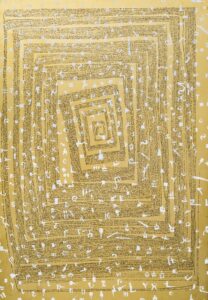

Tra questi l’amore per la materia, resa protagonista in sottolineate stratificazioni, e parallelamente quello per la scrittura, che nella ripetizione del segno passa da significato a significante, sino ad assumere l’aspetto di un grafismo, quasi un pittogramma, dalla valenza estetica e simbolica. Nei lavori di Tania la scrittura è infatti elemento nodale della composizione e, al pari della nota musicale, offre infinite combinazioni che si offrono eleganti e sempre nuove alla vista dello spettatore; un rimando che ne trascende il significato e conduce piuttosto all’idea stessa della scrittura, alla sua componente più strutturale: un “alfabeto possibile” (come è stato definito il suo lavoro), meta-scrittura che acquista valore estetico grazie ai codici dell’arte.

Non stupisce che in parallelo, proprio in nome di un’attenzione alla struttura delle cose, Tania abbia sviluppato uno spiccato interesse per la materia, con la quale mantiene un approccio fisico, un corpo a corpo che risulta evidente nelle sue tele, connotate da stratificazioni, raschiature, applicazioni, sbiancamenti, colle a vista: veri e propri palinsesti di ascendenza medioevale in cui si costruisce per sottrazione: l’effetto finale è il risultato di un processo che molto racconta di chi l’ha eseguito. Il fattore Tempo gioca qui un ruolo essenziale: la pittura – così come il gioiello – restituiscono l’immagine di una “fatica del fare” che richiede concentrazione e perizia; non ultima si rileva una certa dose di ossessiva ripetizione che si fa metodo esecutivo e coinvolge aspetti emotivi. Nella scrittura svolta dal monaco nel suo studiolo c’è già l’essenza dell’esercizio meditativo: l’espressione “lavoro certosino” indica un lavoro di precisione, lento, che impone grandi capacità e pazienza nella ripetizione nel tempo di segni e linee, sino a lambire i confini del misticismo e della pratica zen.

Nell’ultimo biennio Tania Pistone ha sviluppato un progetto ambizioso e articolato, realizzato in collaborazione con Elisabetta Cipriani e che si declina in bracciali, anelli e orecchini in lastra oro e argento; ogni pezzo è unico: la lastra di cera viene incisa e poi utilizzata per la fusione a cera persa in oro o argento. I simboli dipinti a mano sono realizzati in smalto a freddo. L’ispirazione è tratta dalla serie pittorica Rongorongo (il nome delle iscrizioni della lingua di Rapa Nui, oggi indecifrabile), dipinti che raffigurano un immaginario alfabeto dipinto su lastre di foglia d’oro.

La stratificazione osservata in pittura si ripropone sulla materia preziosa del gioiello: l’’incisione sulla lastra metallica diventa base per una altra scrittura, questa volta in applicazione come un raffinato bassorilievo: una spinta ulteriore alla tridimensionalità e alla rifrazione di luce che allo stesso tempo copre ed esalta la scritta su cui posa. Uno spazio al colore che è citazione delle lacche orientali: smalti dai cromatismi pieni e brillanti, giallo, rosso, blu, bianco, verde, quasi una allusione (o un’astrazione) alle pietre di colore.

Ma le correlazioni non si esauriscono qui: Tania Pistone adotta spesso come base delle sue opere il fondo oro. Presente nei mosaici fin dall’epoca paleocristiana, il fondo oro è stato largamente utilizzato dall’arte bizantina e in Italia appare già dal XII secolo: rispondeva ad esigenze devozionali (come dono del committente) e allo stesso tempo forniva una base di pura luce, compatta e astratta, particolarmente apprezzata nei soggetti sacri per l’effetto mistico. In Oriente come in Occidente l’oro è la terra di mezzo tra uomo e Dio, un limen, una dimensione di pura luce, incontro tra la dimensione umana e quella divina. Spiritualità “visiva”.

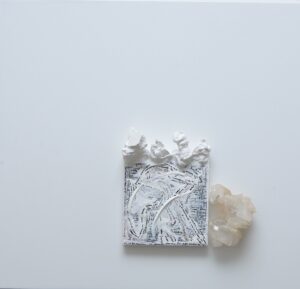

Dal fondo oro al cristallo di rocca l’artista pare inseguire la materia taumaturgica che è luce in essenza: ai cercatori di cristalli, nome che non è frutto di poetica invenzione ma che indica una vera e propria professione (dal XVI sec. nella Svizzera tedesca i cercatori di cristalli sono soprannominati Strahler – o meglio cercatori di luce) è dedicata una serie di lavori in cui il cristallo è addirittura in applicazione sulla superficie, aggettante, segno di quella tridimensionalità che spesso erompe con veemenza dalla doppia dimensione delle tele (talvolta anche con l’inserimento di piccoli oggetti). Il cristallo non è che un ulteriore mezzo che conduce – artista e spettatore – dal pittorico allo scultoreo e, attraverso la preziosità del materiale, allo scultoreo prezioso: un nuovo passo verso il gioiello come arte da indossare.

Gioielli che esprimono il loro carattere plastico nella proporzione fuori scala (come spesso avviene nella fusione a cera persa) come i lunghi orecchini, gli anelli che compiono eleganti volute, o gli alti bracciali da portare in coppia che ricordano quelli alla schiava o evocano ornamenti per riti sacri.

Ne parliamo con l’artista, che ci accoglie nel suo studio.

L’interesse per la pittura (supportata anche da un pronunciato carattere materico fatto di sovrapposizioni e accumulazioni) è sempre stato un punto nodale della tua ricerca; puoi ricordarci brevemente il tuo percorso?

Se investi un profondo senso di coinvolgimento, qualcosa di creativo può accadere; nel mio caso è stata la pittura con le prime mostre all’inizio del 1997.La ricerca e la sperimentazione che si compie per raggiungere il mondo interiore che vogliamo esprimere, diventa uno dei tanti infiniti percorsi che l’arte (in tutte le sue forme) mette a disposizione.La pittura, la scrittura e il segno, mi permettono nello stesso momento di dedicarmi a loro, segno e scrittura in particolare, sono il pretesto per complicare la superficie. Questo è uno dei lussi che ha concesso l’arte moderna e contemporanea.

Ci sono opere del passato che sono state oggetto di ispirazione, sia nel campo della storia dell’arte come in quello della letteratura, data la forte componente della scrittura nei tuoi lavori?

Certamente, una realtà dipinta è una realtà a sé. Condividi con chi osserva ciò che vedi nel mondo in cui lo vedi e questo inevitabilmente ti attraversa e in modo inconsapevole un bel giorno, ritorna e ti ispira. Se si passeggia in qualche museo nel mondo che percorre tutti i secoli della storia dell’arte, non si potrà tornare a casa, rimanendo la stessa persona di prima, nel bene e nel male, ovviamente. La stessa cosa (nel mio caso) per la letteratura, ad esempio un libro che mi ha ispirato e che ritorna spesso, è quello di Italo Calvino, Lezioni Americane, oppure Robert Walser, con le sue Microgramme.

Come sei arrivata al progetto di “gioiello da indossare” Rongorongo, scrittura di Rapa Nui ad oggi non ancora codificata?

Il progetto dei gioielli è nato quando ho realizzato le opere su tavola a foglia d’oro, dei supporti perfetti, pronti ad accogliere scritte e simboli (o ideogrammi), con l’intento di giungere ad un alfabeto ideale, in questo caso da indossare come una seconda pelle, e dove i metalli preziosi, gli smalti e le incisioni agiscono da calamita per accogliere i simboli.

Noto che inevitabilmente anche i tuoi gioielli mantengono il carattere del pezzo unico, proprio per il carattere pittorico che sei riuscita a trasferire in essi: qual è il tuo approccio alle diverse discipline? Noti differenze o una sorta di continuità formale che adatti a supporti differenti?

La continuità formale che adatto ai diversi supporti è certamente la strada che ho preferito, è divertente, e mi permette di sperimentare. Per questo il gioiello è unico; inoltre l’incisione della lastra di cera per la fusione esige che venga incisa da me, la scrittura prima e la pittura con gli smalti dopo, come per le opere pittoriche, diventando in questo caso delle sculture portabili. Il mio approccio è lo stesso che uso in pittura.

Le tue opere dimostrano un profondo equilibrio tra arte occidentale e filosofie orientali, così come tra pittura e scultura, anche grazie all’inserimento di materiali come il cristallo di rocca: puoi parlarci di questa compenetrazione tra discipline e visioni?

Qualcuno ha detto che non bisogna pensare ad una separatezza tra le arti nei secoli, il dialogo è in un continuum spazio temporale. Lo condivido; amo pensare che Bruce Nauman e Fra Angelico avrebbero trovato molte cose da dirsi. Quindi sperimentare tra occidente e oriente è uno dei tanti modi per trovare dialoghi e svilupparli. I cristalli di rocca sono comparsi in relazione ad una mostra a Londra, che aveva come tema la materia e la luce: ho dedicato i lavori agli Strahler – (o meglio cercatori di luce) e alle microgramme di Robert Walser.

Cos’è il gioiello per te?

Un bell’oggetto da osservare nella forma e nel materiale, la storia del gioiello inoltre svela molte storie interessanti, sul suo utilizzo nei secoli.

Si dice che il nome originale della scrittura Rongorongo fosse kohau motu mo rongorongo, “linee incise per cantare”, concetto che trovo molto appropriato al senso mistico rituale del segno grafico come talismano presente nei tuoi gioielli: quale concetto vorresti fosse trasferito a chi indossa i tuoi gioielli?

Il concetto della arcaicità, come un ponte tra due mondi, un tentativo dell’uomo moderno di recuperare la visione di quel mondo che ancora vive in noi. Per me molto accade, in questo punto di “mezzo”.

Come si sta evolvendo la tua ricerca? Arriverai ad un alfabeto codificato?

Sarebbe bello. È un progetto in cui ancora mi perdo, vince il gesto.

La stratificazione, il palinsesto è un processo creativo centrale nei tuoi lavori…Quando l’opera è finita per te?

Quando guardandola, suona come una trombetta.

PER INFO

Tania Pistone’s jewels: wearable writing.

It is always a matter of great interest to observe how an artist manages to transfer poetics into the various disciplines, respecting all formal conditions imposed by material and technique, yet, at the same time, maintaining a basic coherence: Tania Pistone, talented painter who has oriented her research towards a decisive abstraction (a rich, reasoned abstract, far from certain minimalist drifts), has been able to convey in the jewel, with completely original results, some of her specific interests, now distinctive features of her painting.

Among these, her love for matter, made protagonist by insistent stratifications, and, at the same time, that for writing, which in the repetition of a sign, passes from meaning to signifier until it takes on the appearance of a graphism, almost a pictogram, with an aesthetic and symbolic value. In Tania’s works, writing is in fact a key element of the composition and, just like the musical note, it offers infinite combinations that present themselves with elegance and are always new to the viewer’s sight; a reference that transcends meaning and leads to the very idea of writing, to its more structural component: a “possible alphabet” (as her work has been defined), a meta-writing that acquires aesthetic value thanks to the codes of art.

It is not surprising that in parallel, precisely in the name of her attention to the structure of things, Tania has developed a keen interest in matter, with which she maintains a physical approach, a melee which is evident in her canvases, characterized by stratifications, scrapings, applications, bleaching, exposed glues: real palimpsests of medieval ancestry in which one builds by subtraction: the final effect is the result of a process that tells a lot about those who performed it. The time-factor plays an essential role here: paintings – and jewels – restore the image of a “labour in doing” that requires concentration and skill; last but not least there is a certain amount of obsessive repetition which becomes a method of executing and involves emotional aspects. Inside the writing carried out by a monk in his study, we find the essence of the meditative practise: the expression “Carthusian job” indicates a work of precision, slow, meticulous, which requires great skill and patience in the repetition over time of signs and lines, caressing the edges of mysticism and the Zen practice.

In the last two years, Tania Pistone has developed an ambitious and articulated project, created in collaboration with Elisabetta Cipriani Wearable Art Gallery and which consists of bracelets, rings and earrings in gold and silver plate. Each piece is unique: the wax plate is engraved and then used for lost-wax casting in gold or silver. The hand painted symbols are made in cold enamel. Inspiration comes from the Rongorongo pictorial series (the name of the inscriptions in the language of Rapa Nui, still undecipherable) paintings depicting an imaginary alphabet painted on gold leaf.

The stratification observed in the paintings is re-proposed on the precious material of the jewel: the engraving on the metal plate becomes the base for another kind of writing, this time applied as a refined bas-relief: a further push towards three-dimensionality and the refraction of light that simultaneously covers and enhances the marks on which it lands. A space for colour that is a reference to oriental lacquers: enamels with full and bright chromatics, yellow, red, blue, white, green, almost an allusion (or an abstraction) to coloured precious stones.

But the correlations do not end here: Tania Pistone often adopts a gold background for her works. Present in mosaics since the early Christian era, gold as background was widely used in Byzantine art and appears in Italy as early as the 12th century: it responded to devotional needs (as a gift from who commissioned it) and at the same time provided a base of pure light, compact and abstract, particularly appreciated in sacred subjects for the mystical effect. In the East as in the West, gold is the middle ground between man and God, a limen (threshold), a dimension of pure light, an encounter between the human and divine dimensions. A visual “spirituality.

From gold backgrounds to rock crystal, the artist seems to be following the thaumaturgical material which is light in its essence: dedicated to “crystal prospectors”, a name that is not the result of poetic invention but which indicates a real profession (from the 16th century in German-speaking part of Switzerland the prospectors of quartz are nicknamed Strahler – or rather light seekers) is a series of works in which rock crystal is even applied to the surface, jutting out, a sign of that three-dimensionality that often bursts vehemently from the two-dimensioned canvases (sometimes even with the insertion of small objects). Crystal is just another medium that leads – artist and spectator – from the pictorial to the sculptural and, through the preciousness of the material, to a precious sculpture: a new step towards the jewel as a wearable art.

Jewels that express their plastic character in out-of-scale proportions (as often happens in lost-wax casting) such as long earrings, rings with elegant spirals, or high bracelets worn in pairs like manchette cuffs or which evoke ornaments for sacred rites.

Let’s talk about it with the artist, who welcomes us into her studio.

Your interest in painting (also supported by a pronounced material feature made of superimpositions and accumulations) has always been a focal point of your research; would you briefly descried how it started?

If you invest a deep sense of involvement, something creative will happen; in my case it was painting for my first exhibitions at the beginning of 1997. The research and experimentation that is undergone to reach the inner world that we want to express, becomes one of the many infinite paths that art (in all its forms) provides us.

Painting, writing and signs allow me to dedicate myself to them in one sole moment, in particular signs and writing are the pretext to complicate the surface. This is one of the luxuries that modern and contemporary art have granted.

Are there works from the past that provide inspiration, both in the field of art history and in that of literature, given the strong component of writing in your works?

Certainly, a painted reality is a reality in itself. Share with those who observe what you see, in the world in which you see it, and this will inevitably pass through you, even unconsciously one day, it comes back and inspires you. If you walk through a museum anywhere, that spans out all the centuries of art history, you will not be able to go home remaining the same person, for better or for worse, of course. The same thing (in my case) for literature, for example a book that inspired me and that comes to mind often, is that of Italo Calvino’s Lezioni Americane (‘Six Memos for the Next Millennium’), or Robert Walser and his Micrograms.

How did you come about the Rongorongo “wearable jewel” project, in Rapa Nui’s not yet deciphered writing?

This jewellery project was born when I created my works on gold leaf plate, the perfect support, ready to welcome writing and symbols (or ideograms), with the aim of providing an ideal alphabet, in this case to wear like a second skin, and where precious metals, enamels and engravings act as magnets in fitting these symbols.

I notice your jewels inevitably maintain the feature of being unique pieces, precisely because of the pictorial character that you have managed to transfer into them: what is your approach to the various disciplines? Do you see differences or a sort of formal continuity you adapt to each material?

I certainly prefer adapting to the different supporting materials a formal continuity, it’s fun and allows me to experiment. This is why the jewel is unique; in addition, the engraving of the wax for casting requires the plate be engraved by me, first with the writing and then by painting with enamels, just like art paintings, becoming in this case portable sculptures. I use the same approach as when I paint.

Your work shows a profound balance between Western art and Eastern philosophies, as well as between painting and sculpture, also thanks to the inclusion of materials such as rock crystal: can you tell us about this interpenetration between disciplines and visions?

Someone said that we must not think of a separation between the arts over the centuries, dialogue is in a space-time continuum. I share this; I like to think that Bruce Nauman and Fra’ Angelico would have found many things to say to each other. So, experimenting between West and East is one of the many ways to find dialogues and develop them. Rock crystals appeared in connection with an exhibition in London, which had matter and light as its theme: I dedicated my works to the Strahler – (or rather light seeker) and to Robert Walser’s Micrograms.

What is the jewel for you?

A beautiful object to observe in shape and material, the history of the jewel also reveals many interesting stories about its use over the centuries.

It is said that the original name of the Rongorongo writing was kohau motu mo rongorongo, “lines engraved to be sung”, a concept that I find very appropriate in the mystical sense of the ritual of the graphic sign as a talisman, present in your jewellery: what concept would you like to be transferred to the wearer of your jewels?

The concept of archaicity, as a bridge between two worlds, is an attempt by modern man to recover the vision of that world that still lives inside us. For me, a lot happens at this “in-between” point.

How is your research evolving? Will you come up with a coded alphabet?

That would be nice. It’s a project in which I still lose myself, where the signs win.

The stratification, the palimpsest is a focal creative process in your work. When is the piece finished according to you?

When looking at it, I hear like a trumpet sound.

FOR INFO

CANALE ARTE Arte, mercato, aste minuto per minuto

CANALE ARTE Arte, mercato, aste minuto per minuto