STROLL DOWN FOR ENGLISH VERSION; all the photo are courtesy of the artist.

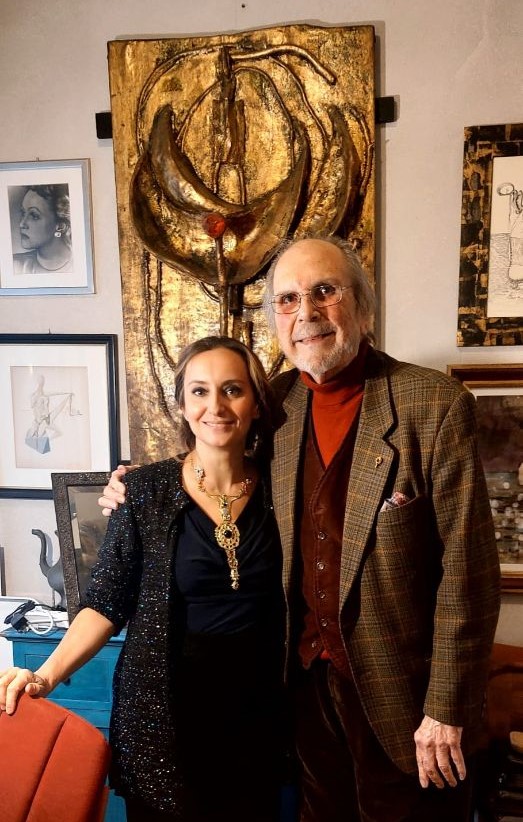

Incontriamo Domingo De La Cueva (l’Avana, 1934) sull’isola della Giudecca, dove il maestro vive da decenni: la Giudecca è “l’isola dell’isola”, separata da Venezia dal suo Canale più ampio e navigabile, che sfocia nel bacino di San Marco; il profilo delle sue case è una quinta meravigliosa per chi osserva l’orizzonte dalle Zattere, con l’elegante imponenza del Molino Stucky, svettante e fiabesco, della leggendaria Casa dei Tre Oci e della Chiesa del Ss. Redentore, amatissima dai veneziani. Un luogo che ha sempre giocato un ruolo di singolare eccentricità: persino sul ferro delle gondole, che presenta sul profilo stilizzato del Canal Grande numerosi decori disposti a pettine a simboleggiare i sestieri e le tre isole maggiori – Murano, Burano e Torcello – la Giudecca è il dente “isolato”, che guarda verso l’interno.

Non poteva esserci luogo più magico ed esotico per ospitare e accogliere un artista nato a Cuba: altra isola, altri mari (eppure sempre luoghi sospesi nell’acqua), che evoca, al solo nome, un mondo mitico, per molte ragioni.

Negli anni Sessanta la Giudecca, e in particolare la zona intorno alle Zitelle (nome dell’antica chiesa palladiana e della fermata del vaporetto) ha visto una concentrazione di artisti, poeti, scrittori, fotografi, tutti richiamati dal fascino della citata Casa dei Tre Oci, curioso edificio neogotico progettato nel 1913 da Mario de Maria in ricordo della figlia, e da Casa Frollo, una sorta di pensione e centro culturale (ruolo che hanno mantenuto per diversi decenni), entrambi aperti all’ampia e cosmopolita comunità di artisti che lì gravitavano e si riunivano sin dalla metà degli anni ‘50. De La Cueva è custode di molti ricordi, aneddoti, vicende e nomi che qui hanno abitato e creato, come l’artista Gianni Pappacena e la pittrice e poetessa austriaca Marianne Tischler, detta anche “Manina”o “Mutti”, figlia del pittore Victor Tischler e del soprano Matilde Ehrlich, grande amica di entrambi. Luoghi e persone che rivivono nei racconti straordinari di Domingo, artista di grande talento, raffinatissimo disegnatore e incisore, scultore e maestro orafo, autore di gioielli frutto di un’immaginazione onirica e fantastica, che esulano da ogni catalogazione stilistica.

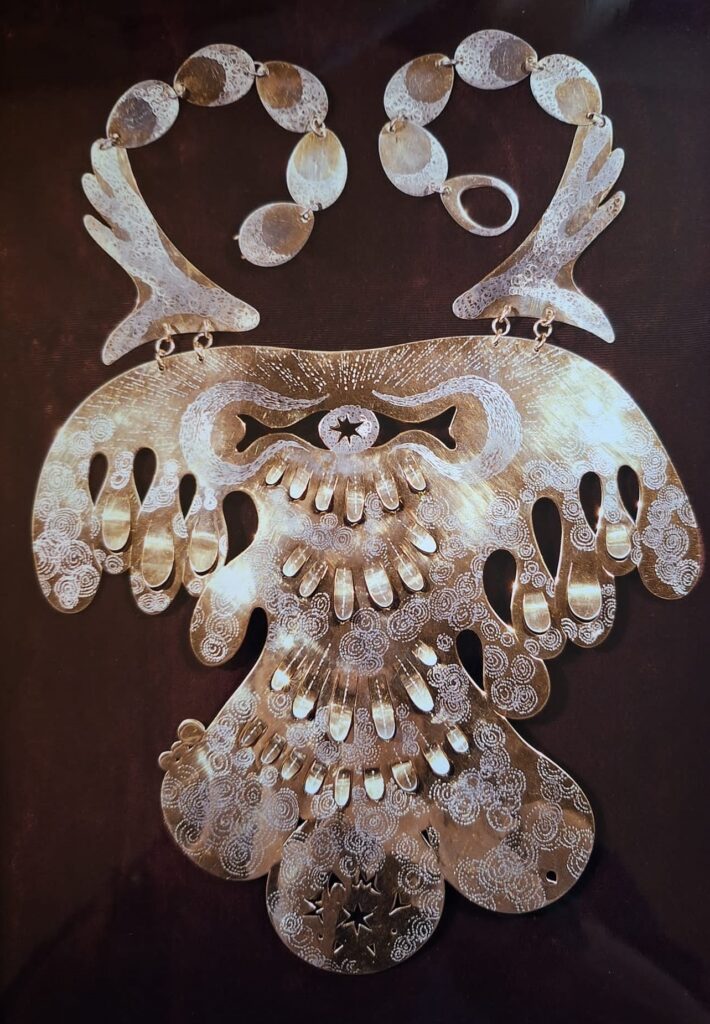

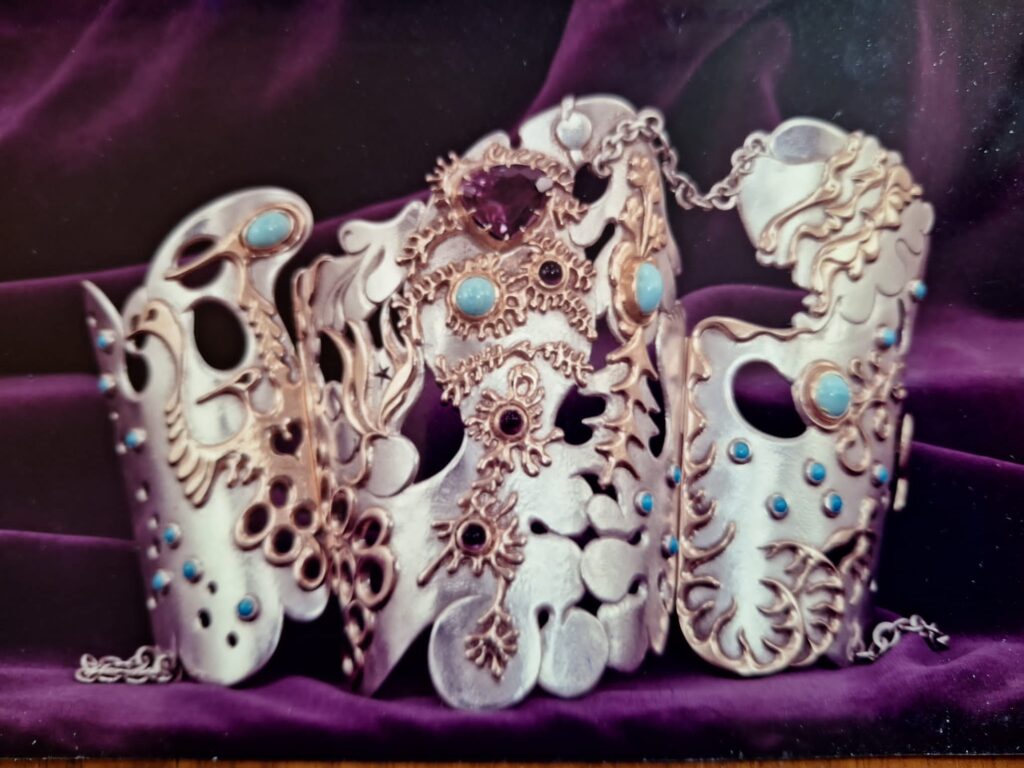

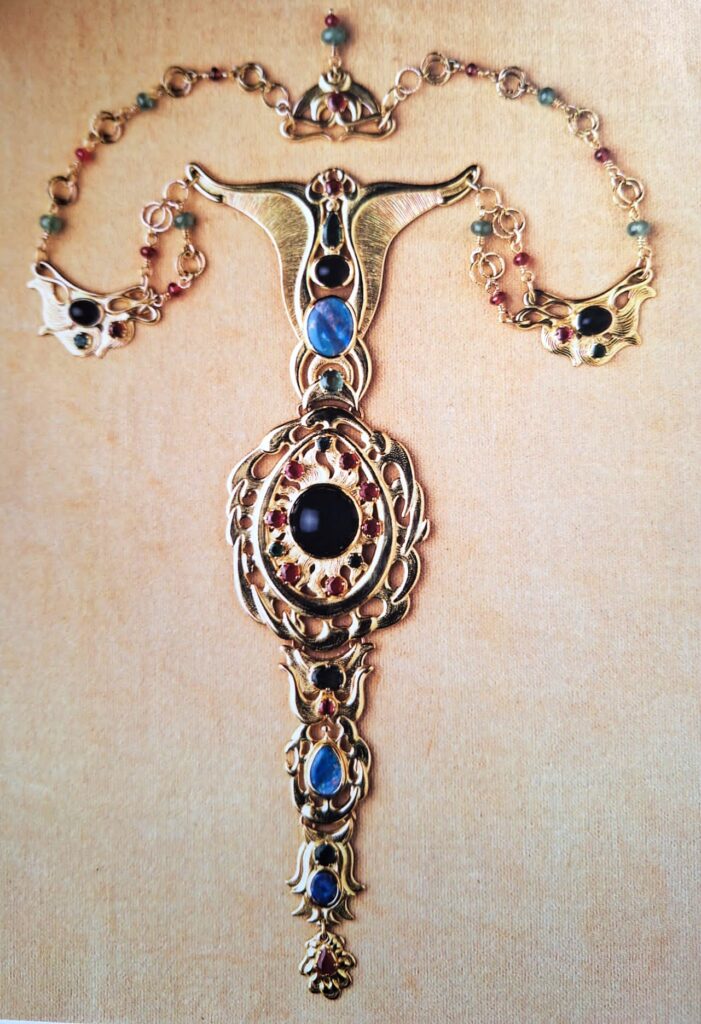

Domingo non dimentica le radici del Centro America ma le trasfigura all’ombra di una cultura apolide, eclettica, ricettiva dei molti stimoli intellettuali ricevuti, che guarda al linguaggio surrealista e al contempo alle forme sinuose del barocco con disinvolta eleganza, nelle quali inserire, con mano sicura, simboli misteriosi di perdute civiltà, vere o di pura invenzione. Nei suoi gioielli, di chiara impronta organica, mondo vegetale e mondo animale si compenetrano in metamorfosi fluide che danno vita a boccioli, uova, ali di farfalla, lacrime, occhi spalancati, organi femminili e maschili… Oro e pietre preziose, spesso rese ancora più seducenti dal taglio cabochon, abbelliscono con le loro cromie e lucentezze un mondo fantastico, di cui solo Domingo ha le coordinate.

Gioielli spesso pensati per ricoprire tutto il corpo come fantastiche armature archeo-futuriste (si veda la splendida “Armatura di Eros”, indossata dalla modella Samantha Jones all’inizio degli anni ’70), veri e propri macro ornamenti adatti a surreali rappresentazioni sceniche. Un talento coltivato nei laboratori veneziani all’inizio degli anni ’60 (Domingo si era trasferito da Cuba a Venezia per seguire corsi di architettura, che lasciò per l’arte orafa) e che ebbe un grande riscontro critico alla Biennale del 1964, dove vinse il Primo Premio per le Arti decorative, a pari merito con Mario Pinton, già maestro e fondatore della celebre Scuola di Padova. Tra le sue estimatrici Peggy Guggenheim, che così definì i suoi gioielli, cogliendone l’estrema leggerezza e allo stesso tempo l’originalità compositiva, impossibile da catalogare: “Domingo de la Cueva’s fantastic jewels belong to all ages and are very much alive. In fact so much so, that one feels they might at any moment take wing and fly away”.

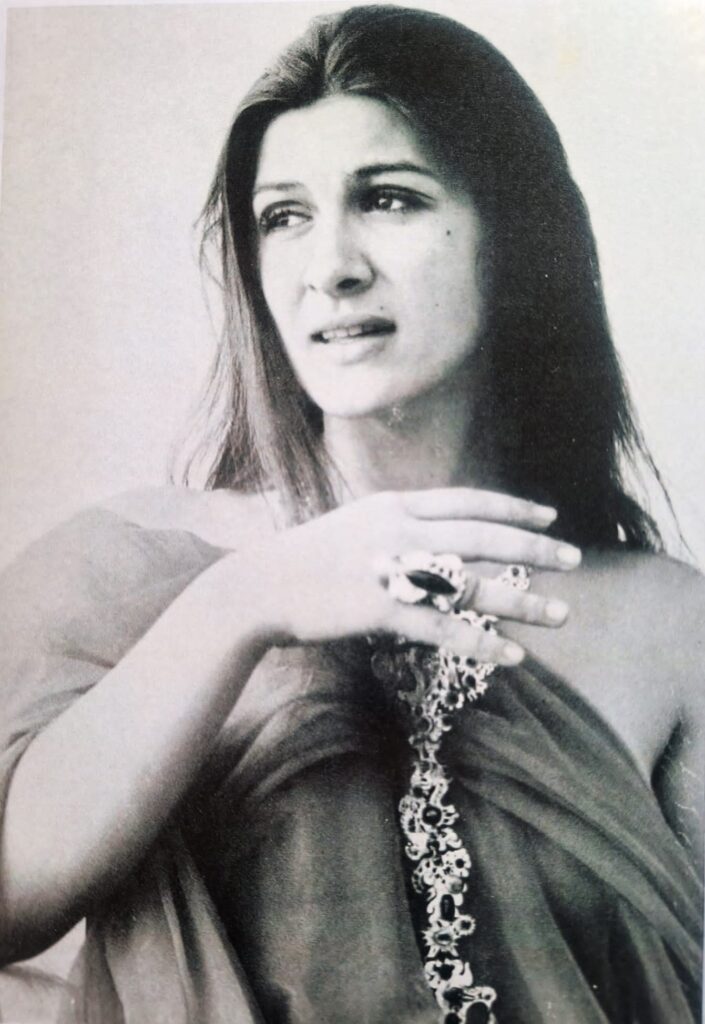

Le sue creazioni, fastose ed eccentriche, furono presto richieste per importanti servizi di moda sulle più rinomate riviste dell’epoca, a partire da Vogue; celebre poi l’immagine di una giovanissima Paloma Picasso che indossa un suo gioiello-scultura proprio sulla Terrazza della Casa dei Tre Oci: la fotografia è del 1967 ed è stata scattata da John Loring, già direttore artistico di Tiffany’s. La stessa Paloma dichiarerà, anni dopo, che la conoscenza con Domingo influenzò in modo significativo la sua attività di disegnatrice di gioielli, ideati proprio per la celebre maison americana.

Tra gli anni ’60 e ’70 le sue opere entrarono in collezioni prestigiose, inclusa quella della Regina Margherita II di Danimarca, Paese dove espose a più riprese, e negli Stati Uniti, dove Domingo soggiornò a più riprese e per lunghi periodi dell’anno; qui ebbe la possibilità di lavorare con Noma Copley, ex moglie del celebre artista e collezionista Bill Copley, che allestì un laboratorio orafo a New York, dove Domingo ebbe modo di praticare la fusione a cera persa e collaborare alla realizzazione dei gioielli della stessa Copley. Qui le creazioni di De La Cueva ebbero grande successo nel mondo della moda e del jet set internazionale, vennero esposte nei musei ed ancora oggi sono conservate in collezioni pubbliche e private; in particolar modo le catene, vero e proprio marchio di fabbrica, conobbero uno straordinario successo negli anni ’70. Immaginate e realizzate da Domingo come lunghissime e avvolgenti, erano spesso decorate da pietre dure o piccole maschere d’oro con la funzione di talismani protettivi, “feticci incatenati”, come usava chiamarli. Lunghe collane pendenti – i Totem – assumevano invece l’aspetto di sculture a “racconto verticale”, giocate sull’alternanza di elementi componibili volutamente diversi e asimmetrici.

Altrettanto significative le sue sculture per il corpo, veri e propri collari, pettorali, lamine preziose modellate sulla figura umana con sensibilità e fantasia. La prima intuizione, come egli stesso racconta, gli venne proprio dalla modellazione di un cartoncino dorato lucido su un manichino mentre si trovava per una sua mostra in Danimarca, grazie alla quale gli risultò immediato rialzare i lembi e creare volumi come fossero metallici piumaggi, forme concave e convesse che vestono il corpo accompagnandone ed esaltandone le curve naturali; ripetere l’esperimento con la lamina d’oro fu l’evoluzione naturale di questo processo, e Domingo lo adottò a molte sue creazioni, volutamente avvolgenti e di grande formato, eppure sempre con un occhio alla portabilità che la componente organica suggeriva. Le sue creazioni assunsero sempre di più il carattere di sculture portabili, allusive, surreali, gioiosamente inquietanti, che celebrano l’essere umano nell’aspetto e nello spirito, come ben espresso da titoli, vere e proprie chiavi per accedere al suo mondo poetico: “Un paradiso interno”, “Meditazione”, “Divinità” “L’impossibile: il Matrimonio del Sole e della Luna”, “Rivelazione del Meraviglioso”.

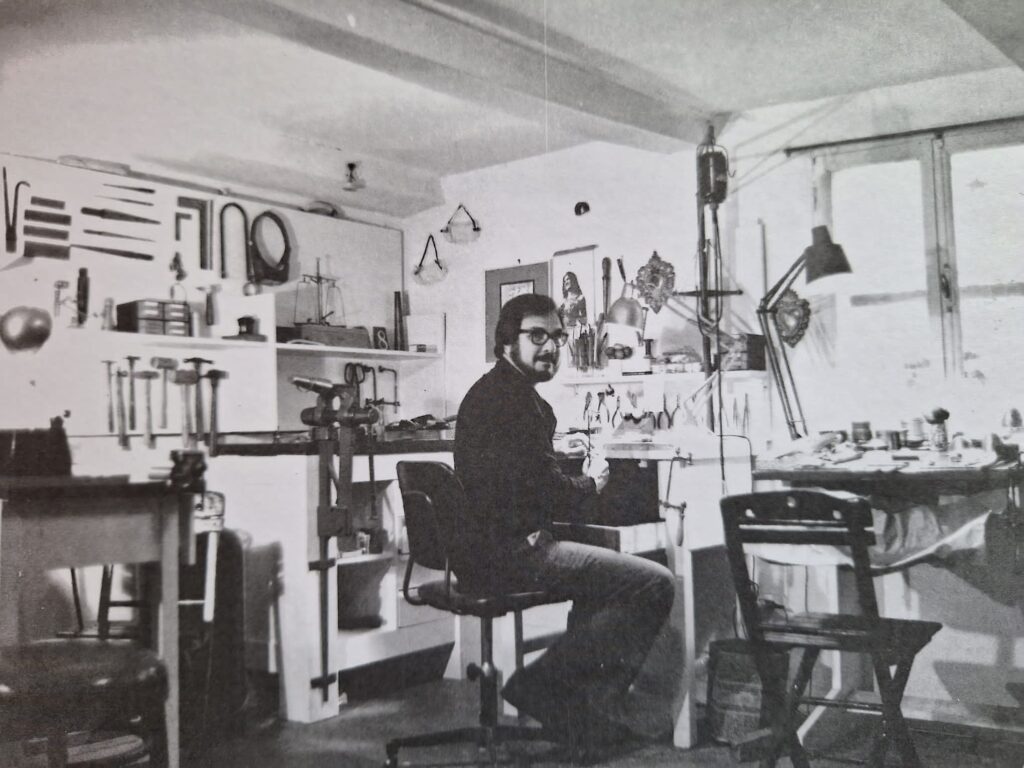

Abbiamo avuto la possibilità di rivolgergli alcune domandi nel suo studio-abitazione alla Giudecca, a cui si accede da un bellissimo e segreto giardino.

Maestro, può ricordarci come hai iniziato a interessarsi ai gioielli?

Sin da bambino sono stato attratto dal disegno e dall’arte; dopo gli studi superiori mi sono iscritto alla Facoltà di Architettura all’Avana e ho frequentato lo studio del pittore Luis Jorge Horstmann, ma sentivo che tutto ciò non mi bastava, desideravo allargare i miei orizzonti e decisi di partire per l’Europa. Dopo un viaggio avventuroso su un mercantile diretto ad Amburgo scelsi di proseguire per l’Italia, in particolare Venezia, dove sapevo esserci un’ottima facoltà di architettura. Qui frequentai alcune lezioni all’università e all’Istituto d’Arte alla Scuola dei Carmini, dove mi avvicinai all’oreficeria. Ebbi uno scontro con un insegnante della scuola e me ne andai con tre spille ancora da terminare; poco dopo entrai in contatto con un laboratorio orafo in centro a Venezia gestito da Franco de Cal, Giorgio Rallo e Alberto Zucchetta, e mi proposi a loro come collaboratore: fu l’inizio di un vero e proprio sodalizio professionale e d’amicizia, che fu determinante per il mio percorso umano e lavorativo.

Nelle sue opere possiamo notare una decisa influenza surrealista. Quali sono le sue fonti di ispirazione e come le applica nella fase creativa?

Il mio atteggiamento verso il mio lavoro è duplice: da una parte molto distaccato, dall’altra quello amorevole di un genitore. Distaccato perché il mio lavoro proviene da una misteriosa fonte interiore che mi usa come mezzo di espressione; amorevole, perché l’opera diventa parte di me per sempre. Il mio metodo di lavoro è quello automatico surrealista. Ho bisogno di essere in uno stato “speciale” per far emergere forme, simboli e immagini che interpreto, scelgo, scarto e assemblo: questa è la parte “intellettuale” della mia creazione. Le selezioni vengono effettuate lavorando direttamente su metallo, o cera, oppure disegnate su carta e poi trasferite nella materia. È difficile determinare di che cosa ho bisogno per cadere in quella speciale condizione, fertile per la creazione. A volte ho bisogno di pace, altre sono stimolato da ansia o desideri insoddisfatti; talvolta mi attrae il mistero delle pietre preziose e semipreziose, o la sfida di completare il microcosmo di una persona con la forza di un gioiello. Nel mio lavoro esprimo l’immenso desiderio che ho per l’ignoto e l’invisibile.

Quali sono state le sue opere più significative, che hanno segnato una “svolta”nel suo percorso artistico?

Certamente le collane Totem sono state un punto nodale nel mio percorso: se le catene erano già molto popolari e raggiunsero la loro massima diffusione tra gli anni sessanta e settanta, le collane a sviluppo verticale furono una novità che piacque moltissimo. Alcune di esse hanno la possibilità di essere modificate nei loro elementi mobili che possono diventare spille o semplicemente accorciarne la lunghezza: in particolare penso al totem in oro e topazi della metà anni degli ’60 che ho chiamato “Dall’uovo all’essere alato”: la collana termina infatti con un piccolo uovo da cui ho immaginato si sviluppasse tutto il resto della composizione.

Quale è stato il suo rapporto con Venezia in tutti questi anni?

Venezia, tante volte sognata e immaginata, è diventata il luogo dell’anima; mi sono riconosciuto subito in essa. Ho amato molto anche gli Stati Uniti, dove il gioiello d’artista è molto apprezzato, collezionato, esposto nei musei. Purtroppo non sono più tornato a Cuba.

Un’ultima domanda, forse la più difficile…Cos’è il gioiello per Lei?

È una domanda complessa: posso dire che chi sceglie un gioiello, inteso come opera d’arte da indossare, compie una decisione istintuale e molto profonda, che parte dal subconscio e deve corrispondere al proprio io, fisico e psichico. Il gioiello d’artista non è un ninnolo, è arte in tutto e per tutto e come tale ne possiede la forza e l’intensità. Penso che il gioiello inteso in questo senso non morirà mai, l’essere umano ne sentirà sempre la necessità: si può stare senza un diamante, ma non senza un gioiello d’artista!

DOMINGO DE LA CUEVA: FROM CUBA TO VENICE, THE ARTIST JEWELS SURREALIST POETRY

We meet Domingo De La Cueva (Havana, 1934) on the Giudecca island, where he has lived for decades: Giudecca is “the island of the island”, separated from Venice by its wider and more navigable Canal, which flows into the basin of San Marco; the profile of its houses is a wonderful backdrop for those who look at the horizon from the Zattere, with the elegant grandeur of the Molino Stucky, soaring and fairytale-like, the legendary Casa dei Tre Oci and the Church of Ss. Redentore, loved by the Venetians. A place that has always played a role of unique eccentricity: even on the iron of the gondolas, which has many decorations arranged in a comb on the Grand Canal stylized shape to symbolize the districts and the three major islands – Murano, Burano and Torcello – the Giudecca is the single tooth, which looks inwards. There could not be a more magical and exotic place to host and welcome an artist born in Cuba: another island, other seas (always places suspended in the water), which evokes, in its name alone, a mythical world, for many reasons.

In the 1960s, Giudecca, and in particular the area around the Zitelle (the name of the ancient Palladian church and the vaporetto stop) saw a concentration of artists, poets, writers, photographers, all attracted by the charm of the aforementioned Casa dei Tre Oci, a curious neo-Gothic building designed in 1913 by Mario de Maria in memory of his daughter, and by Casa Frollo, a guesthouse and cultural center (a role maintained for several decades), both open to the large and cosmopolitan community of artists who gravitated and gathered there since the mid-50s. De La Cueva is the caretaker of many memories, anecdotes, events and names that have lived and created here, such as the artist Gianni Pappacena and the Austrian painter and poet Marianne Tischler, also known as “Manina” or “Mutti”, daughter of the painter Victor Tischler and the soprano Matilde Ehrlich, a great friend of both. Places and people that come to life in the extraordinary stories of Domingo, a very talented artist, refined designer and engraver, sculptor and master goldsmith, author of jewels that are the result of his fantastic imagination, which goes beyond any stylistic cataloguing. Domingo does not forget the roots of Central America but he transfigures them with a stateless, eclectic culture; he takes inspiration from the surrealist language and, at the same time, from the Baroque sinuous forms with nonchalance elegance, adding, with a sure hand, mysterious symbols of lost civilizations, real or pure invention. In his jewels, with a clear organic imprint, the flora and fauna interpenetrate themselves in a fluid metamorphosis that gives life to eggs, butterfly wings, tears, wide open eyes, female and male symbols… Gold and precious stones, often made even more seductive by the cabochon cut, embellish with their colors and shine a fantastic world, of which only Domingo has the right coordinates.

Jewels, often designed in order to cover the whole body as a fantastic archaeo-futurist armors (see the splendid “Armor of Eros”, worn by the model Samantha Jones in the early 70s), are real macro-ornaments suitable for surreal stage representations. A talent cultivated in the Venetian workshops at the beginning of the 60s (Domingo had moved from Cuba to Venice to follow courses in architecture, then left for the goldsmith’s art) and which had a great critical response at the 1964 Biennale, where he won the First Prize for Decorative Arts, with Mario Pinton, former teacher and founder of the famous School of Padua. Among her admirers there was Peggy Guggenheim, who defined his jewels as follows, capturing their extreme lightness and at the same time their compositional originality, impossible to classify: “Domingo De La Cueva’s fantastic jewels belong to all ages and are very much alive. In fact, so much so, that one feels they might at any moment take wing and fly away“. His creations, sumptuous and eccentric, were soon requested for important fashion shoots for the most renowned magazines of the time, such as Vogue. The image of a very young Paloma Picasso wearing one of his jewel-sculptures right on the Terrace of the Casa dei Tre Oci is very famous too: the picture was taken in 1967 by John Loring, former artistic director of Tiffany’s. Paloma herself would declare, years later, that her acquaintance with Domingo significantly influenced her work as a designer of jewels for this famous American jewelry maison.

Between the ’60s and ’70s his works entered prestigious collections, including the Queen Margarethe II of Denmark’s one, and in the United States, where Domingo stayed several times and for long periods of the year; here he had the opportunity to work with Noma Copley, ex-wife of the famous artist and collector Bill Copley, who set up a goldsmith’s workshop in New York, where Domingo had the opportunity to practice lost-wax casting and collaborate in the creation of Copley’s jewels. Here De La Cueva’s creations had great success in the world of fashion and the international jet set, and they were exhibited in many museums. In particular the chains, his trademark, were extraordinarily successful in the 70s. Imagined and made by Domingo as very long and enveloping, they were often decorated with semi-precious stones or small gold masks with the function of protective talismans, “chained fetishes”, as he used to call them. On the other hand, long pendant necklaces – the Totems – look as “vertical story” sculptures, played on the alternation of deliberately different and asymmetrical modular elements. Equally significant are his sculptures for the body, collars, pectorals, precious sheets shaped on the human figure with sensitivity and imagination. The first intuition, as he himself recalled, came from the modeling of a shiny golden cardboard on a mannequin while he was in Denmark for an exhibition: he started to raise the flaps creating new volumes as metallic plumages, concave and convex shapes that dress the body. As natural evolution of this process he repeated the experiment with gold foils; after then he adopted it for many of his creations, yet always with an eye to the portability that the organic component suggested. His creations increasingly took on the character of wearable, allusive, surreal, joyfully but disturbing sculptures, which celebrate the human being in appearance and spirit, as well expressed by titles, real keys to access his poetic world: “An Inner Paradise”, “Meditation”, “Divinity” “The Impossible: The Marriage of the Sun and the Moon”, “Revelation of the Wonderful”.

We had the chance to ask him a few questions in his studio-home, which is accessed from a beautiful and secret garden on Giudecca island.

Can you talk about your first interest in jewelry?

Since I was a child I have been attracted by drawing and art; after high school I enrolled in the Faculty of Architecture in Havana and attended the studio of the painter Luis Jorge Orstmann, but I felt that all this was not enough for me, I wanted to broaden my horizons; I decided to leave for Europe. After an adventurous voyage on a merchant ship for Hamburg, I chose to continue to Italy, in particular Venice, where I knew there was an excellent faculty of architecture. Here I attended some lectures at the University and at the Art Institute at the Scuola dei Carmini, where I approached goldsmithing. I had a conflict with a teacher at the school and I decided to leave it with three brooches still to be finished; shortly afterwards I came into contact with a goldsmith’s workshop in the center of Venice run by Franco de Cal, Giorgio Rallo and Alberto Zucchetta, and I proposed myself to them as a collaborator: it was the beginning of a real professional partnership and a strong friendship, which was decisive for my human and professional path.

What are your sources of inspiration and how do you apply them in the creative phase?

My attitude towards my work is a dual one: on the one part very detached, on the other hand the loving attitude of a moter-father. Detached because my work comes from a mysterious inner source that uses me as a means of expression; loving, because is cominga part of me forever.

My working method of working is the Surrealist automatic one. I need to be in a “special” state to let shapes, messages, symbols and images emerge. With these I interpret, choose, discard and assemble. This is the “intellectual” part of my creation. The selections are made by working directly on metal, or wax, or designed on paper and then transleted. It is difficult to determine what I need to fall into that special state, fertile for creation. Sometimes I need peace, within and without. Sometimes it can anxiety or unfulfilled desires; other times the mystery in precious or semi-precious stones spread out, or the challenge of completing a one person’s microcosm with a jewel. In my work I fulfil myself and the immense longing I have for the unknown and the unseen.

What were your most significant works, which marked a “turning point” in your artistic journey?

The Totem necklaces were a nodal point in my path: if chains were already very popular and reached their maximum diffusion between ’60 and ’70, the vertical necklaces were a novelty that became immediately very popular. Some of them have the possibility of being modified in their mobile elements: you can get brooches or you can simply short their length: in particular I’m thinking about the golden totem with topaz of the mid-60s that I called “From the egg to the winged being”: the necklace ends with a small egg from which I imagined the rest of the composition.

What has been your relationship with Venice in all these years?

Venice, so often dreamed and imagined, has become the soul place; I immediately recognized myself in it. I also loved the United States, where the artist’s jewel is highly appreciated, collected, exhibited in museums. Unfortunately, I never returned to Cuba.

One last question, maybe the most difficult one… What is jewelry for you?

It is a complex question: when you choose a jewel, intended as a work of art to wear, you take an instinctual and very deep decision, which starts from the subconscious: it must correspond to your physical and psychic state. In my opinion the artist’s jewel is not a trinket, it is art and, as art, has a particular strength and intensity. I think that jewelry will never die, human beings will always feel the need to get it: you can stay without a diamond, but not without an artist’s jewel!

CANALE ARTE Arte, mercato, aste minuto per minuto

CANALE ARTE Arte, mercato, aste minuto per minuto